Last spring, Center Field ran a three-part series that focused on the Marist men’s basketball program during the mid 1980s—its most successful period. There was no surprise that the run of winning coincided with Rik Smits’ time in Poughkeepsie, but what some people don’t know is that former Marist coach Mike Perry broke NCAA recruiting rules to land Smits and other players.

At nearly 10,000 words, this is the comprehensive account of what really happened during the golden age of Marist men’s basketball.

By Jonathan Kinane • Published in the Spring of 2022

Part 1: Trouble in Po-Town

It’s March 5, 1987, a chilly night in Poughkeepsie, New York. Inside the McCann Center, the atmosphere was anything but cold; it was electric.

A sellout crowd had assembled to watch Marist take on Fairleigh Dickinson for the ECAC Metro title and a bid to the NCAA Tournament. When the buzzer sounded, and the Red Foxes came away with a 64-55 win, it might have been the peak of the men’s basketball program, less than a decade into the team’s tenure in Division I.

Players celebrated, and fans stormed the court and lifted head coach Dave Magarity onto their shoulders as Marist earned its second consecutive trip to the Big Dance. Led by the gigantic duo of 7-foot-3 Rik Smits and 6-foot-11 Miroslav Pecarski, the Red Foxes reeled off 14 straight wins after finding the trio of Smits, Pecarski, and Rudy Bourgarel suspended at the beginning of the season.

If you’re a student, try to imagine an atmosphere like this in McCann. If you’re a longtime fan, think about how the last 35 years have mostly been downhill from here.

From the 1984-85 season through to ‘86-87, Marist fielded three of its best teams in program history, earned two conference titles, and won 60 percent of its games. On paper, it seems like this should have some kind of peaceful golden age for Marist basketball. On the court, it was, but off of it, those three years were anything but tranquil.

There were numerous coaching changes, recruiting violations, and scandals that led to the suspensions of Smits, Pecarski, and Bourgarel. The NCAA was breathing down Marist’s neck.

Indeed, to understand why Marist found itself in such a sticky situation heading into ‘86-87, you have to rewind a couple of years.

It all started at the end of the 1983-84 season when head coach Ron Petro decided to get about as far away from Marist as he could while still living under the American flag. Petro amassed a 226-238 record over 18 seasons in Poughkeepsie and helped guide the Red Foxes from Division III to Division I. After his third season at the top level, Petro bolted to become the athletic director at Division II Alaska Anchorage for a $64,000 salary, an amount too good to pass up.

Coincidentally, Alaska Anchorage had recently been put on NCAA probation for recruiting violations. Petro’s successor would make sure Marist suffered a similar fate.

Anchorage, Alaska sits 1,944 miles away from Marist’s campus. Mike Perry came from coaching a pro team in Paris, some 3,500 miles across the Atlantic, to assume the head coaching role in Poughkeepsie.

“This is probably the most important day of my life,” Perry said at his introductory press conference in March 1984. “It’s a great situation. I’m very impressed with what I’ve seen here and the people I’ll be working with.”

In 18 seasons of coaching, Perry never posted a losing season, leaving with a 408-158 record. His connections in Europe allowed him to recruit the “triple towers” that would dwarf other teams in the ECAC Metro Conference.

Perry got the job because of his supposed recruiting acumen. His philosophy was that Marist should look to the European market to recruit players because it could not compete for top talent stateside.

“This was long before a lot of other schools were recruiting European guys,” said Paul Kelly, who covered the team for The Circle, during the ‘86-87 season. “Perry had some connections, and Marist said, ‘Let’s try to fast track our way into Division I and get some of these guys.’”

Perry pledged to deliver a 7-foot-3 European player that could change the trajectory of the program. That savior’s name was Gunther Behnke from Leverkusen, Germany.

“Who the hell is Gunther Behnke?” That’s probably the question you’re asking.

Well, he was the top international center in that year’s recruiting class. Most fans have no idea who Behnke was because getting him to tiny Marist was a pipe dream, considering who the Red Foxes were up against for his services.

“That was part of the reason (Perry) got the job,” said Ian O’Connor, who was the sports editor for the campus newspaper during the ‘84-85 school year. “I believe he told the Marist administrators that he had a good shot to get Gunther Behnke, who ended up at Kentucky.”

The consolation prize was another supposedly 7-foot-3 giant, who grew up in Holland dreaming of becoming a motorbike mechanic. O’Connor quickly learned that Smits was actually 7-foot-4.

“I remember the first time I ever wrote his name in The Circle,” said O’Connor, who has enjoyed a decorated career in journalism and now writes for the New York Post. “I think I listed him at seven-three. So the next day in the cafeteria, I heard this deep voice, and I felt this figure behind me.

“He called my name. I turned around. It was Rik just standing right over me. Seven-foot four as he’s about to tell me. He said, in a very deep voice, ‘Ian, I’m 7-foot-4, not 7-foot-3,’ and that was the end of that.”

While talent evaluators didn’t know it at the time, Behnke would flop stateside, not appearing in a single game for Kentucky after getting homesick for his native Deutschland and not coming over to play in the NBA despite being drafted on two separate occasions. Smits, on the other hand, ended up blossoming into the second overall pick in the 1988 NBA Draft after four spectacular years in Poughkeepsie.

“I remember watching Rik play after Mike Perry had brought him in,” O’Connor said. “You could see right away, I think I wrote in The Circle, that this guy is going to be a future first-round pick, and some of my roommates were laughing at me. It was amazing to see how much better he got in like three weeks. I said if this guy can walk and chew gum with that size, he’s going to play in the NBA.”

Even at tiny Marist, the gargantuan Smits was not the most-touted player in his recruiting class. That honor belonged to Pecarski, who hailed from Yugoslavia and came in as the more polished player.

“I remember Pecarski coming in with some more hype around him,” Kelly said. “There was a good basketball culture in Yugoslavia, and he had been playing for longer than Rik and definitely had more game at that point in their careers. Then, he broke his foot before that season, and Rik caught up, to say the least.”

Even without Pecarski, things still looked promising for Perry’s inaugural season. But there was a problem. A big problem.

Perry violated NCAA rules to deliver Smits, Pecarski, and later, Rudy Bourgarel—current NBA star Rudy Gobert’s father. Perry is likely one of the most infamous figures in the history of Marist athletics. That is all the more impressive when you factor in that he failed to coach a single game or practice.

It turned out that Perry did things like buying rum-and-Cokes for Smits’s parents in a restaurant in Eindhoven, allowing players to use his phone for long-distance calls back home, and arranging for Smits to stay at the home of a member of the Marist College Board of Trustees while the dorms were closed.

Perry also had assistant coach Bogdan Jovicic meet the newcomers—Smits, Pecarski, and Alain Forestier from France—in New York City. Jovicic later admitted to buying the players Burger King on the trip back to Poughkeepsie. Perry also sent him to New York to buy winter coats for two of the players (with their money, not his).

These actions by Perry and Jovicic all counted as NCAA violations. They were all minor transgressions that added up to about $770 in monetary value, not very much when considering the excessive money that many high-level football recruits received around that same time.

“It was a lot of minor-league stuff,” Kelly remembers. “We definitely weren’t talking bags of cash or anything like that. I remember hearing words like minor and inadvertent. There were schools out there that were definitely doing more, but Marist was for sure breaking the rules.”

Perry might have been able to continue his low-level crime if it wasn’t for one weekend in New York City. Perry and Forestier shared a hotel room, and according to Don Yeager’s Undue Process: The NCAA’s Injustice for All, the player accused the coach of making a sexual advance during the weekend.

Perry denied anything happened, but the incident derailed his short tenure and exposed the minor violations. Forestier filed a complaint with Joseph Belanger, a Marist brother, and foreign-student advisor. In the Nov. 8, 1984 edition of The Circle, Belanger claimed not to know anything about a personal complaint. That didn’t stop him from taking action when he heard of the violations.

“I’m not the first faculty member who was told of the incidents by the player but only the first one to act,” Belanger said to The Circle. “I’m unsure, but I believe that there were at least three others who the player told before me.”

Belanger finally took action and called Marist College President Dennis J. Murray, telling him about the violations. Murray met with Perry in late September. The audience said a lot about Perry’s character.

From Undue Process:

“Perry made no bones about breaking the rules, arguing that if Marist really wanted to compete with the big boys, it had to play the game his way. ‘He seemed to indicate that he would continue, that that was the only way you could get ahead, that the regulations were crazy,’ Gerard Cox, vice president of student affairs, said.”

Perry had the opportunity to apologize, to say he messed up. He didn’t take it. On Friday, Sept. 28, 1984, Murray asked for and received Perry’s resignation. Mike Perry’s short, disastrous, yet strikingly influential tenure was over. He would do everything he could to make sure that Marist regretted its decision to part ways.

“I remember hearing that Perry was just sort of a shady guy,” Kelly said. “And the way he recruited and his attitudes about breaking the rules just kind of confirmed that.”

O’Connor covered the saga for the The Circle and remembers Perry’s firing a bit differently than Undue Process, which claimed the violations had more to do with the coach’s departure than Forestier’s complaint.

“I remember what the personal complaint was, the nature of it,” O’Connor said. “I wasn’t allowed to print it, but he was not fired because of an NCAA violation, he was fired because of that complaint.”

O’Connor and Circle faculty advisor David McCraw (who now works as a lawyer for the New York Times) were summoned to Murray’s office, where they met for a short time. It was a sensitive case, with lawyers ready to jump in at a moment’s notice, but Murray granted O’Connor the first interview, ahead of the Poughkeepsie Journal.

“My first question was, is it true that Mike Perry was fired because of a personal complaint filed by a player against him? And Dennis Murray got pretty angry, and he said, ‘If that’s going to be your line of questioning, we’re gonna have a problem here,’” O’Connor remembers.

The story ran on the front page of the Oct. 4, 1984 edition of the The Circle, with the title, “Player’s complaint plays key role in Perry’s exit.”

From the story:

“In a Monday morning meeting with Circle editors, Murray was asked if Perry had a personal problem with any of the players. To that, Murray replied, ‘No, not to my knowledge.’ The president was then asked if Perry had a personal relationship with any of the players. Once again, Murray said, ‘No, not to my knowledge.’”

At the end of the story, Murray said, “It’s just unfortunate. You might even classify this incident as tragic.”

Murray called the NCAA and reported the violations soon after Perry’s forced resignation. In doing the right thing, Murray ensured that the Mike Perry saga would continue well past Perry’s Tenure at Marist.

By chance, O’Connor saw Murray soon after the story ran. They were the only walkers on an empty path, headed right toward each other. But instead of a showdown, Murray stopped to shake O’Connor’s hand.

“Basically, I was saying that the college was not completely forthcoming, and there are reasons for firing the coach,” O’Connor said. “And he had no problem with it. So that told me that what I wrote that, it was basically his way of confirming it.”

Marist was now without a coach and athletic director just weeks before the regular season and days before the first official practice. With such a short turnaround, who would coach the Red Foxes in the ‘84-85 season?

The answer was Matt Furjanic, the bespectacled, balding head coach at Robert Morris University, an ECAC Metro foe.

The 35-year-old Furjanic had plenty of success in the Pittsburgh suburbs, leading the Colonials to back-to-back- NCAA Tournament bids in 1982 and 1983. He didn’t need to go elsewhere to find success but he did if he wanted a bigger payday.

I was making $22,000 at Robert Morris and my contract at Marist was $36,000,” Furjanic said. “So that obviously had a little bit to do with it, but Marist also had a good recruiting class coming in that season, and I thought it would be very interesting to coach a couple of big guys in that league.”

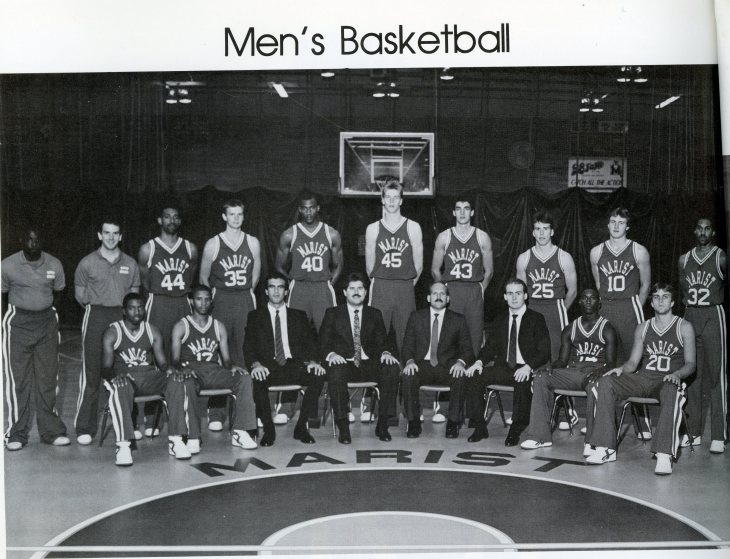

The ‘84-85 team was an amalgamation of talented young players and experienced upperclassmen. Seniors Ted Taylor and Steve Eggink were joined by the international newcomers who Furjanic was excited to coach: Smits, Forestier, and the injured Pecarski.

Even though Furjanic was the third coach in six months, the timing of the Perry resignation didn’t really complicate things for the players. Since Perry never ran a practice or instituted a system, the team only had to adjust to Furjanic’s system. It was the start of a run of truly talented Marist teams.

The Red Foxes won in both seasons under Furjanic. In ‘84-85, they won their first regular-season conference title in Division I. They also played Villanova close, losing 56-51 early in the season. The Wildcats would end up winning the national title in upset fashion over Patrick Ewing’s Georgetown Hoyas.

Marist finished the regular season 16-11 and 11-3 in the ECAC Metro. A trip to the NCAA Tournament, however, would need to wait. The Red Foxes lost a heartbreaking 56-55 contest in double overtime to Loyola in the semifinals of the conference tournament.

“I think, overall, that team was one of the best, certainly the top-three,” Eggink said. “Overall in Marist’s Division I history, I mean. I don’t think too many people would argue. It was a great team. It was a tough ticket for a lot of friends that weren’t basketball players.”

Eggink transitioned to the sidelines as an assistant for the ‘85-86 season, but most of the core remained the same. Smits made the all-important jump in his sophomore campaign, and Pecarski returned from the foot injury he suffered the season prior.

Marist overcame a poor out-of-conference record and won 15 out of 19 games to close the season. They won the three that mattered most, grinding out three victories in the ECAC Metro Tournament at Furjanic’s old stomping grounds in Pennsylvania.

Marist Basketball on The Today Show – March 13, 1986

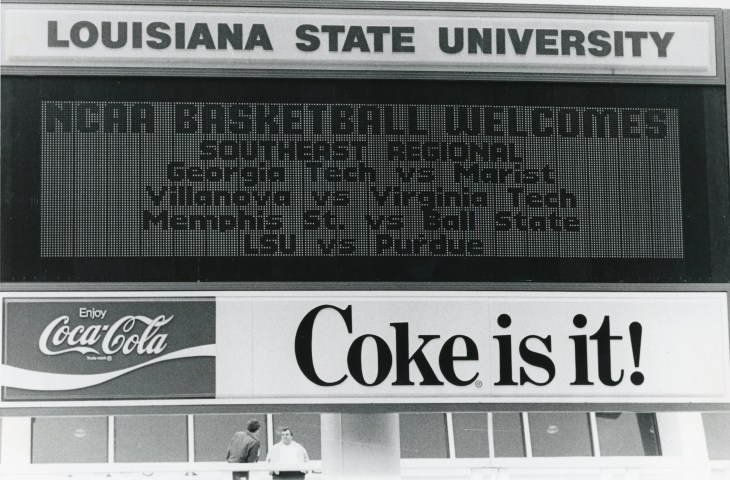

In their first trip to the big dance, the Red Foxes earned a 15-seed in the Southeast Region and had the tall task of Georgia Tech, a top-10 team waiting for them in the first round in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Marist lost a 68-53 decision that was much closer than the scoreboard indicated.

“It was a great game,” Furjanic recalled. “We were right with them at about the 10-minute mark, but then Rik picked up his fourth foul, and we had to take him out when it was a three or four-point game. Then, they went on a run, and it was a 13-point game a couple of minutes later.”

At one point in the second half, Marist held a 38-37 lead over the second-seeded Yellow Jackets. Even after they faded later in the game, the Red Foxes still felt encouraged by their performance.

“We felt that we played them close and gave them a good run,” John McDonough, a sophomore on that team, said. “We thought that we could go a step further next year and win a game.”

So, little Marist acquitted itself quite well on the national stage, the team leaving the court to an ovation from the 10,000 spectators that packed the LSU Assembly Center. If the 7-foot-4 Dutchman had stayed out of foul trouble, it might have even won the game. From an outsider’s perspective, everything looked just fine. All the key contributors were set to come back and play for a coach who was 36-24 in his two years in Poughkeepsie.

Everything was, in fact, not fine.

When people talk about Furjanic, one of the things that always comes up is his intensity.

“He was a fiery coach in that he wasn’t afraid to kind of get in people’s faces rather quickly,” McDonough said. “His gum used to come flying out of his mouth all the time, in games and in practices.”

“Furjanic was one of those really intense coaches,” Kelly added. “He was always moving around, and you know, the team could be up 25 with four seconds left, and he’d be screaming and gesticulating at guys to get to the right spot.”

People who have played sports at any level likely know what it’s like to have an intense coach. In the heat of a close game, coaches scream and yell and stomp and curse, but with Furjanic, it seemed to be a constant flow instead of a rising and falling tide.

Furjanic, for one, never felt a disconnect between himself and the team.

“I never felt anything like that,” he said. “I never heard anything from the team that season. There might have been some guys that didn’t like their roles, but I thought it was a great group of guys that worked really hard.”

At a time when the Cold War was in its final years, Furjanic coached like a tyrant you might have found in the Eastern Bloc.

“A lot of guys just didn’t like him,” McDonough said. “It was more of a dictatorship than anything else. We felt like we never really had our say.”

Things came to a head near the end of the spring semester in 1986. In late April, the team met with senior college administrators to discuss Furjanic’s handling of the roster. Several players made it clear that they would leave the program if Furjanic remained in charge.

In the May 1, 1986 edition of the Circle, Marist athletic director Brian Colleary said, “There’s definitely discontent spreading among members of the men’s basketball program. It’s been magnified throughout the year.”

Several players threatened to leave if Furjanic remained in charge. The college was faced with a difficult decision: get rid of a winning coach to please the players or keep the coach and risk losing some of the team’s best talent.

As O’Connor wrote in The Circle, “You can’t fire the players, but you can fire the coach.”

In the end, it didn’t come to that. Furjanic resigned his post, citing personal reasons.

“I needed a change,” he said. “I was giving too much attention to the game and not enough to my family. I learned later that I came down with depression and anxiety, and I’ve been getting treated since.”

If he hadn’t been feeling the heat, odds are that Furjanic would have stayed. Originally, he expressed his intent on fulfilling the final season of his three-year contract, even though he applied for three head coaching positions, including the vacancy at Iona College. The climate around the team made that impossible.

So Furjanic was out. Marist was in the market for its fourth coach since the ‘83-84 season. Whoever the successor was, he needed to have one thing above all else: staying power.

The program was already in turmoil, but Perry’s words and actions from after his tenure ended were about to make things even worse for the Red Foxes going into the ‘86-87 season.

Part Two: Steadying the Ship?

In 1986, Washington Post writer John Feinstein published his famous book A Season on the Brink: A Year with Bob Knight and the Indiana Hoosiers. That fall, he found time to write a much smaller story about a much smaller program that also found itself in turmoil despite unprecedented success.

“Marist Caught Short by Suspensions” appeared in print in the Post on Dec. 4, 1986. The 1,000-word article detailed how Marist’s three international big men, nicknamed the “triple towers” had yet to take to the court in the early going of the 1986-87 season.

Knight is still one of the most divisive figures in college basketball. Mike Perry, Marist’s former head coach, wasted no time becoming a controversial figure in his own right and was the reason Marist found itself in trouble as the season began.

It was just two days before the Red Foxes were set to open the season at the Lapchick Tournament at St. John’s when the NCAA declared 7-foot-4 Rik Smits, 6-foot-11 Miroslav Pecarski, and 7-footer Rudy Bourgarel ineligible. Newly minted head coach Dave Magarity found his team full of giants reduced to one of the smaller outfits in the country.

As Magarity pointed out in the Post article: “There’s so much irony in this. None of the people who were involved in this are at Marist now.”

Perry was named head coach in March 1984 but never coached a game or even a practice. When allegations of sexual harassment toward a player and illegal recruiting methods came to light, Perry had to resign in late September of that same year.

Without an athletic director on the staff, Marist President Dennis J. Murray called the NCAA and reported the recruiting violations.

In February 1985, the NCAA sent an investigator to Poughkeepsie. After two days, he concluded that Murray was doing the best he could to address the problems that Perry had caused. Eventually, thanks to some haggling from Murray, the NCAA decided to let Marist off with a public reprimand, a slap on the wrist of sorts.

What came next was straight out of a serial killer movie. Here’s an excerpt from Undue Process: The NCAA’s Injustice for All by Don Yeager.

“In September 1985, a day before the public reprimand was scheduled to be announced, Murray received an anonymous letter detailing further rules violations. The same day, Smits received a postcard telling him to transfer because Marist was ‘in trouble with the NCAA.’ The card was signed ‘a friend.’”

The anonymous author and the friend were, of course, the same person. After Marist requested a handwriting analysis of the postcard, it was determined that Perry was the unnamed writer. Things got worse when Murray saw a newspaper article that had an interview with the disgraced ex-coach, in which Perry said that the NCAA had never contacted him during the investigation.

“It’s impossible that the NCAA could have investigated without contacting me,” Perry said in that day’s Poughkeepsie Journal. “If they had asked me what happened, the investigation might still be going on.”

On top of Perry’s initial wave of known transgressions, it later emerged that he purchased Smits’s airfare to the United States, a definite no-no by NCAA rules.

In the Dec. 12, 1986 edition of the Circle, Murray all but confirmed the purchase of the plane ticket, saying, “I won’t refuse (the allegations), but I can’t discuss specifics.”

Perry’s response when reached for comment: “How does he know that? I’d like to see him prove it.”

A few weeks after his firing, Perry told the Kingston Freeman that he “had probably committed 40 other violations” during his brief tenure.

“I think that was his way of saying that the violations weren’t a big deal,” said Ian O’Connor, a Marist graduate who now writes for the New York Post. “If I remember, it was something to the effect of, ‘if you want to get technical about it, I probably made a number of violations.’ I think it was his way of saying that the NCAA rulebook was silly.”

Perry might have thought the violations were a joke, but the NCAA certainly wasn’t laughing.

Until that day in late September, Perry had somehow managed to escape from detection from the NCAA. After he was forced out, he vacationed in Florida for a couple of weeks before returning to Kingston, right across the Hudson River.

Days before he moved to Hawaii to sell novelties on the beach, Perry told the Florida Times-Union, “It wouldn’t have been tough at all to find me. It’s curious that the media never had a problem finding me and the NCAA couldn’t.”

Perry passed away in 2002. He was 63 years old.

Again, Murray did the right thing and contacted the NCAA, asking them to put off the announcement of the public reprimand until it talked to Perry.

After it spoke to Perry, the decision would be much worse than a public reprimand. It would also be almost two years until Murray heard anything from the NCAA Committee on Infractions.

While all that was going on, Magarity was preparing for his first season as head coach at Marist. The former Iona assistant was introduced on June 10, 1986, and was everything that his successor, Matt Furjanic, was not.

“Magarity, when he came, he was awesome,” Smits said to Center Field in 2019. “We got along really well. Furjanic was more of a guy that didn’t get close with his players. He let his assistants try to get close. But Magarity was close. He really felt like he wasn’t only your coach but your friend and your mentor. And I responded to that really well. We still talk a couple of times a year. I consider him a friend for the rest of my life.”

“The players responded to him because he was probably as much of a player’s coach as a college coach could be,” added Paul Kelly, sports editor of the Marist Circle during the ‘86-87 season. “Dave was, from what I recall, was much less of a drill sergeant than Furjanic, and the guys played hard for him.”

Magarity’s background as a player endeared him to the roster.

“He wanted the best out of his players and he knew how to handle them,” said John McDonough, who played at Marist from 1984-88. “Furjanic didn’t give a crap who he stepped on and how he stepped on him. Magarity wanted things done his way, but he also understood the other side because he was a player.”

Magarity’s first task was a tall one. Literally. Smits returned to his hometown of Eindhoven in the Netherlands, his Marist future very much up in the air.

After getting national exposure for the first time following the 1986 NCAA Tournament game against Georgia Tech, Smits had his fair share of options. Sure, he could remain at little Marist, but he also could have transferred or gone pro in Europe. It was up to Magarity to woo him back to Poughkeepsie.

“Dave literally went over to Holland and re-recruited Rik,” Tim Murray, an assistant on the ‘86-87 team said. “Because Rik played so well against Georgia Tech in the NCAA Tournament on a national stage, everyone was like, ‘Wow, this kid’s pretty good.’ Dave was worried about losing Rik and some other guys, but he had great relationships with the players, and I think that was the reason why so many of the guys came back.”

So, Smits came back. Alain Forestier, who submitted the complaint against Perry, left the program, but the rest of the roster was intact. Smits and Pecarski naturally drew a lot of attention for their size and skill, but the Red Foxes returned other key pieces who were instrumental in the success the team would achieve in Magarity’s first season.

Ron McCants and Drafton Davis anchored the backcourt. McCants was the scorer, and Davis was the floor general who preferred to pass instead of shoot. Davis ended up being one of the leading assist men in the country for the ‘86-87 season, dishing out eight helpers per game.

To supplement the frontcourt, Marist had Peter Krasovec, a Hungarian import, and Mark Shamley. Krasovec made 34-of-73 from behind the three-point line (just 19 feet, 9 inches in those days) and averaged nearly 10 points per game. Shamley was the kind of forward that was never flashy but always consistent. His seven points and five rebounds per night cannot go understated.

Marist’s full roster was better than anyone else’s in the ECAC Metro and could challenge a good number of power conference teams, even some of the so-called bluebloods.

The problem, of course, was that Marist didn’t have its full roster for the first part of the season.

A little over a week before the Red Foxes’ season-opener, everything still seemed alright. Then, on Nov. 21, 1986, Marist athletic director Brian Colleary got a call from the NCAA. The message: “Marist has some serious eligibility issues to deal with.”

The issues concerned Smits, Pecarski, and Bourgarel, all Perry recruits. Four days after Colleary got that call, the NCAA told Marist that it must declare the three foreign big men ineligible. There was an expectation that the NCAA would promptly reinstate the players. That expectation proved to be incorrect.

On November 26, the NCAA announced that Smits was suspended indefinitely and that Pecarski and Bourgarel would each receive seven-game bans.

Nobody took the news very well.

“We were all over the place because nobody understood it,” said McDonough. “There was so much uncertainty about it. We didn’t know what was gonna happen. You know, we heard everything from kids getting a one-game suspension to the program was going to shut down.”

It fell on Magarity, who took the job without knowledge of the NCAA violations, to comfort and reassure a shaken team.

“Dave’s immediate reaction was to console the kids,” said Tim Murray, who has been Marist’s athletic director since 1995. “We weren’t here when it happened. We couldn’t control it. Marist was doing the best it could from an administrative level to deal with it, but we just had to worry about the kids.”

Even if Magarity quieted his team’s worries, what was left of the roster had to make the coach sweat a little bit. In the blink of an eye, the Red Foxes went from one of the tallest teams in the country to one of the smallest.

With guys like Shamley and Krasovec left to fill the massive gaps down low, Marist’s dreams of becoming the first team other than St. John’s (the tournament host) to win the season-opening Lapchick Tournament were quickly dashed.

“We had to make a lot of adjustments to the game plan,” said Jeff Bower, the assistant coach known for being the “x’s and o’s guy.” “With the big guys out we had to rely a lot more on the backcourt, and we had to go to more of an up-and-down style of play.”

The Red Foxes lost to Youngstown State in the first game, then again to Southern the next night for an 0-2 start. Marist’s most successful season in the last 35 years was off to an inauspicious beginning.

Marist sat at 2-3 for the season on Dec. 11, 1986, its roster still very much in limbo. The Red Foxes didn’t play a game that day, yet it proved to be one of the most important moments of the season.

December 11 was the day the NCAA Subcommittee on Eligibility heard Marist’s appeal regarding Smits, Pecarski, and Bourgarel. While Pecarski and Bourgarel were due to be back in a few more games, Smits was still suspended indefinitely. If Marist failed to get the decision overturned, then the “Dunking Dutchman’s” future in Poughkeepsie was in serious jeopardy.

Colleary told the Dec. 12, 1986 edition of the Circle that Smits would be permanently ineligible if the appeal failed. It was a tense few days.

In the same edition of the Circle, there was another bombshell. The program committed more violations after the Perry era. The rule-breaking happened during Furjanic’s tenure, but the balding, bespectacled head coach was not complicit in the events.

Bogdan Jovicic, the Yugoslavian assistant coach who Perry sent to New York to buy winter coats in the fall of 1984, had stayed on the staff after Perry was forced out. Jovicic was spotted at a summer league game that featured Smits and Pecarski in 1985.

He had given Smits and Pecarski a ride to the game at City College in New York City, breaking another NCAA rule.

There were also more free long-distance calls for European players, one of the things that Perry was cited for allowing. The violations were all pretty minor, but they were more ammunition that the NCAA could use against Marist.

When he looked back on his Marist career with Center Field in 2019, Smits mentioned that he was told not to be transparent during the first part of the investigation.

“At the time, we were just impressionable kids who did what our athletic director told us to do,” Smits said. “We put our trust into him, and it didn’t work out too good, unfortunately. He didn’t know how to deal with it, either.”

“He made some wrong choices that ended up costing us. Costing me nine games. And us. Not everyone got suspended maybe, but I know personally I would not have gotten penalized as much as I did if it just did what was right, right from the beginning. We were told to say certain things, and we went with it. And it backfired on us, unfortunately.”

According to Smits, it was Colleary who told the players to obfuscate rather than come out and tell the truth about the things Perry had done during his brief tenure.

Dennis Murray was upfront with the NCAA when he learned about the violations. He did things by the book. Somewhere along the way, this approach changed. Later on, Marist brought in a lawyer who promptly told the players that they need to tell the NCAA the truth.

The accumulating list of infractions would come back to bite the Red Foxes in the not-so-distant future, but for the time being, Marist won a major victory when the NCAA curbed Smits’s indefinite suspension to nine games.

Pecarski and Bourgarel also got to come back earlier, but everyone knew that Smits would have the biggest impact.

Smits wouldn’t be back until the new year, which meant the Red Foxes still had to grind out the remainder of their non-conference schedule without him.

The nadir of the ‘86-87 season came in Utica, New York, two days before Christmas. The Red Foxes cratered inside Utica College’s Clark Athletic Center, losing 59-57 to a team that didn’t have a conference and stopped competing in Division I after the ‘86-87 season.

“I remember Dave telling me that he hated games before Christmas because he never knew what he was going to get from his team,” Tim Murray said. “The kids wanted to go home and see their loved ones. Sure enough, we were terrible. It was a dark day.”

Everything changed when Smits returned. Without the 7-foot-4 Dutchman, the Red Foxes were a team that could make it to the ECAC Metro playoffs, but not much further. With him, they were head and shoulders above the league.

By January of 1987, Smits was no longer the raw prospect imported from Holland. After many late nights in McCann, he had slowly blossomed into a skilled post player. Jeff Bower, one of Magarity’s assistants, put in countless hours working with Smits and the rest of the team.

“I think we spent a lot of time doing individual work and trying to work on things that were going to be needed for him to continue to grow as a player,” said Bower, who later to went on to work for several teams in the NBA. And whatever areas that Rik wanted to try to refine and improve defined how we went about developing a way to do that.”

Kelly, who ran track on top of his duties with the Circle, remembers seeing Bower and Smits burning the midnight oil on the court.

“He would be down there working with Rik on his post moves,” Kelly said. “I can remember him like having football blocking pads because Rik came from Europe, and they weren’t physical in Europe, and they had to get Rik used to taking a beating. Man, did that guy work hard through all his four years.”

Back in 1987, the Red Foxes actually lost their first game with Smits in the lineup. Marist sat at 3-7 through 10 games, but a change was about to come.

“When we got Rik back, we could actually run the plays we’d been working on for months,” said Murray, the assistant. “With him, we knew we were the best team in the league.”

Some games were close, others weren’t, but a three-game streak became six, and six games became 10. After a 61-57 victory at Robert Morris on February 28, Marist had closed the regular season with 12 straight wins to sit at 18-9 on the year.

Twelve straight wins were great. A program record at the Division I level. But for that to mean anything to the team, Marist would need to add two more victories to that streak at the ECAC Metro playoffs to clinch a return trip to the NCAA’s.

This time, the team thought it could do some damage.

Part Three: It All Comes Crashing Down

It may seem difficult to imagine today, but the McCann Center was a very intimidating place to play when the Marist men’s basketball team took the floor back in the mid-1980s.

McCann isn’t quite a tinderbox like other small college gyms, but the fans were still close to the court, and the students turned up in droves to support their team. Contrary to what it is now, Marist was the epitome of a mid-major powerhouse as it rolled into the 1986-87 ECAC Metro Tournament.

“McCann was packed every game,” said Paul Kelly, who covered the team for the Marist Circle. “People knew that this team was good. People in Poughkeepsie got into it, they were there, and the students went. It was awesome. We knew this team was special, we knew Rik was special. This was the year when it became clear that Rik was the best player in program history.”

The Marist madness swept from theater enthusiasts to accounting majors. Sports are one of the few things that can fully unite a college campus. Marist basketball brought a diversified college campus together.

“You really, really, really had to dislike sports, to not get swept up in the men’s basketball fever that year,” Kelly said. “Like it was just almost impossible not to get swept up. It was just exciting because it’s such a small school, and we had a really good player, and everyone just went along for the ride.”

When the 1987 ECAC Metro Tournament came to Poughkeepsie, everyone knew that the Red Foxes, riding a 12-game winning streak, would be that much harder to beat on their home floor.

Unlike conference tournaments today, where pretty much every team gets to go, the ECAC Metro during the 80s only took the top four teams. In 1987, the pecking order was Marist, Fairleigh Dickinson University, Loyola University (Maryland), and Wagner College.

As the top seed and the host, all the pressure was on the Red Foxes. An entire season’s worth of work could be wiped out with a loss in the conference tournament.

“Yeah, I think that was probably the most pressure we felt,” said John McDonough, a junior on the team. “We were at home, and we were the big favorites to win, playing in front of a packed house at McCann. It was definitely the most pressure I felt in my four years.”

“The only way you’re getting into that damn tournament is to win your conference tournament,” Kelly added. If they lost either of those games, 15-1 in the league would have gone straight down the toilet.”

Marist’s first opponent was Wagner, a Staten Island-based school that the Red Foxes swept in the regular season. As is the case in March, the game was close the whole way, going into overtime before the Red Foxes came away with a 59-57 victory and advanced to the conference championship game the next night.

With the line for tickets going out the door, the Red Foxes’ next opponent was Fairly Dickinson, nicknamed “Fairly Ridiculous” by the students. Marist had also swept FDU in the regular season, but the combined margin of victory in those two games was only five points.

It was another tough game, closer than the final score indicated, but after a 64-55 victory, Marist was headed back to the dance.

“It was pure elation,” McDonough said. “We were ecstatic. We thought we could go in there and build off last year’s performance [a 68-55 loss to Georgia Tech].”

Marist basketball hasn’t experienced that rush, that high that comes with winning such a big game, since that night in early March 1987.

Still, even though the Red Foxes had kept their winning streak alive, extending it to 14 games, they were by no means invincible.

“They damn near lost to Wagner and needed overtime to get past them, and FDU was another close one,” Kelly said. “There were two close calls there. I remember there was just on campus there was a bit of hubris, you know, FDU could be tough, but we should roll over Wagner. Those close calls in the ECAC Metro were definitely a bit of a reality check.”

Things wouldn’t be any easier once Dave Magarity and his team learned that their opponents in the first round of the NCAA Tournament had a guy who could do this.

Marist earned the 14-seed in the West Region of the 1987 NCAA Tournament, setting up a first-round clash with the third-seeded Pittsburgh Panthers. Being in the West Region meant a trip to Tucson, Arizona, a welcome change from Poughkeepsie in March.

Pittsburgh was a member of the Big East, the best conference in the country during the late 80s. They played a tough, bullying brand of basketball that the Red Foxes did not see in the ECAC Metro, where they were the bullies themselves.

While Marist had height, Pitt had size with the backboard-shattering Jerome Lane at forward and the hulking Charles Smith in the middle.

It wasn’t even close. Marist jumped out to a quick lead but suffered terrible foul trouble, with Smits racking up three first-half fouls and Rudy Bourgarel picking up four personals in the first 20 minutes. The Red Foxes trailed 39-21 at the half and lost the game 93-68.

“We just threw up on ourselves,” McDonough said. “I don’t know what it was. You know, they were a good team. I mean, they had Charles Smith and Jerome Lane. They could play, but we laid an egg. It was a game everyone wanted to have back.”

“They overpowered us. Literally. Rik got in foul trouble early, which was really disappointing because everything we were doing worked around Rik,” said Tim Murray, an assistant coach on the team. “We had a really hard time scoring, and I just don’t think we were as prepared as we would have liked to have been. It was disappointing we didn’t make a better show.”

Right or wrong, those 40 minutes (the loss to Pitt) defined Marist’s season for just about everyone outside the program. In the words of Kelly in the Apr. 5, 1987 edition of the Circle: “Unfortunately, for schools like Marist… memories of a 30-game season are encapsulated into one 40-minute endeavor. And for Marist, it was one 40-minute nightmare.”

Also, from Kelly in that same article:

“Build those crosses with the realization that Marist basketball was more than a game this season. A simple child’s game united this community as nothing ever has.

“For once, a MacGregor basketball, not IBM, controlled our region. For three days in March, everyone at Marist had the same major — Red Fox basketball — and saw it played at the highest level in a 4,000 seat classroom.

“Then, the four-lettered demon resurrected itself. NCAA.”

While Kelly was talking about the tournament loss, his words would prove prescient for the offseason.

After over a year of silence, the NCAA was finally ready to levy its punishment on Marist for the violations during the Mike Perry and Matt Furjanic eras.

In May, the decision was still pending due to “the reluctance of some individuals” (Perry was one of them) to cooperate with the NCAA. Students went home for the summer not knowing the verdict, but by the first weeks of the fall semester, the ruling hit like a ton of bricks.

On Sept. 10, 1987, Marist athletic director Brian Colleary received a letter from the NCAA detailing the penalties for the 14 rules violations committed under the two previous head coaches.

The violations, which occurred mostly under Perry, included the purchase of over $600 in clothing for two student-athletes, various purchases of meals, and automobile transportation for two players to play in a summer league game in New York City. There was also free use of athletic department telephones for international players to make long-distance calls and the organization of team workouts before the permissible start date of October 15 during the 1984-85 season.

The NCAA hit Marist with probation and banned them from the postseason for two years. The college could appeal, but if the decision stood, it meant that the team could not go back to the NCAA Tournament in Smits’s final season.

Assistant coach Bogdan Jovicic, who specialized in recruiting foreign players, was banned from off-campus recruiting for the next two years. He himself bought the clothes for the recruits and provided the meals and transportation to the summer league games.

To make things worse, Jovicic initially denied his involvement to the investigators before coming clean later.

“After denying involvement in these (recruiting) violations, at a later time, he admitted his involvement in the violations,” the report read. “The violations were serious, and the repeated giving of false information to the institution and the NCAA made the situation far worse.”

Jovicic, a native of what was Yugoslavia, did not have a firm grasp of the NCAA rulebook.

“I was not familiar with any NCAA rules,” he said. “The second time I told them I made a mistake. I did apologize for that mistake.”

Predictably, the reaction to the NCAA’s punishment was swift and negative.

Colleary called the penalties “grossly excessive and without precedent,” especially since Marist got rid of Perry and self-reported the violations.

In the appeal to the NCAA, Marist officials wrote:

“The case against Marist College is unprecedented in the history of the NCAA because of the many mistakes and the misconduct of the NCAA staff in handling this investigation. From the very beginning of this case, NCAA staff provided incomplete and/or inaccurate advice to college officials, have not been forthright in admitting these errors, and have attempted to fabricate a major case against Marist College to cover up their own inappropriate activities.”

Marist had been an underdog in the previous two NCAA Tournaments, but this was a different kind of battle against a much mightier Goliath in the form of the NCAA.

After such a unifying experience the season before, Marist students once again joined together to express anger with the decision. For the players, it was a familiar sense of “why us?”

“Again there was a sense of disappointment and frustration with the rulings,” McDonough said. “As seniors, we felt we could make another run, and even though the school filed an appeal, it was still something that hung over us all season.”

Like the previous season, the onus fell on Magarity to pick up the team’s spirit after an NCAA intervention. This was more than suspensions to Smits and Pecarski, this was the NCAA saying, “you can play, but your season won’t mean anything.”

Once again, Magarity tried to make the best of a bad situation.

“Dave did his best to turn things around,” Murray said. “He made the team believe again. He talked about potentially winning the appeal, but even if the decision stood, just having the best team we could. We tried not to dwell on it because it had nothing to do with us.”

“Dave kept us together,” McDonough added. “We might have been naive college kids, but he led us to believe, to keep playing. He said, ‘let’s play hard because there’s a chance we can get this overturned.’ We bought in, even though it was always hanging over our heads.”

Even though Smits returned, Marist lost a pair of international players, highlighted by the absence of Pecarski.

Pecarski, who would have been a senior, remained in his native Yugoslavia to prepare for the 1988 Summer Olympics, with hopes of playing on his national team. The 6-foot-11 forward averaged 12.4 points and 8.4 rebounds per game during the 1986-87 season. He ended up returning to Poughkeepsie for the ‘88-89 campaign.

Peter Krasovec, who would have been a junior, was the other player who stayed in Europe. Krasovec, a Hungarian, had to stay in his home country to fulfill compulsory military service when Hungary was still a satellite of the Soviet Union.

Even with some new faces forced into action and a difficult out-of-conference schedule, Marist still put together another solid season, even with the specter of the penalties following them everywhere they went.

In January, with the basketball team beginning its ECAC Metro schedule, Marist officials, including president Dennis Murray and athletic director Brian Colleary, went before the NCAA Council for an appeal of the original decision.

The cards were stacked against Marist in advance.

From Don Yeager’s Undue Process: The NCAA’s Injustice for All:

“In their efforts to prepare for the appeal, Marist officials asked for a copy of the tape-recorded infractions committee hearing. They were told that the only way they could hear the tapes was if they flew to Kansas City and listened to them in an NCAA office. Once there, they were told they could not take any notes on the tape verbatim.”

On top of that, the Marist delegation only had 20 minutes (the length of an oral argument in the Supreme Court) to present their case about a three-year-long investigation.

Marist lost the appeal and any hopes of making it to the postseason in Smits’s final year.

The Red Foxes finished the year 18-9 and 13-3 in conference play, coming in second to Fairleigh Dickinson. Marist closed out the season with a narrow win over Robert Morris at McCann on senior night. Still, it was a premature end to a season that should have been remembered for more solid basketball.

Marist never had a chance against the NCAA. In basketball terms, it was like a 16-seed taking one a 1-seed in March Madness. Except the 1-seed was allowed to play with two extra guys on the court and all three referees in its pocket.

It didn’t matter that Marist self-reported the violations, or that Dennis Murray called the NCAA and asked them to talk to Perry when it had failed to do so in its first investigation.

What mattered to the NCAA was a winter coat, a car ride, a cheeseburger, and a fountain soda. These items, in the NCAA’s opinion, gave Marist an unfair advantage in recruiting Smits even though few college coaches knew who he was at the time of his recruitment.

The thing that really made the Marist administration cry foul was the NCAA’s inconsistency with issuing penalties. The exact monetary value of Marist’s violations was $773.26. For less than a thousand dollars, the Red Foxes found themselves banned from the postseason and on probation for two years.

UCLA, a very proud basketball program a little more than a decade removed from a national title, committed 10 violations that totaled up to $2,600. The NCAA ruled on UCLA’s case a week after they issued the decision on Marist.

Using Marist’s punishment as a baseline, the Bruins should have gotten harsher penalties than the Red Foxes. Instead, the NCAA censured UCLA, basically slapping them on the wrist and allowing them to compete in the postseason.

The difference was that UCLA drew attention and high television ratings and was a national brand. Few people outside the northeast knew of Marist College.

For a few golden years in the mid-1980s, Marist was a powerhouse mid-major program. It got a taste of what it was like to be in the spotlight for the right and wrong reasons. The Red Foxes got to play the role of David for three charming seasons. But in this story, David could never get past Goliath.

Epilogue:

It was January 1990 by the time Marist was finished serving its probation. The ECAC Metro had become the Northeast Conference and Marist was in the middle of a 17-11 season that saw them miss the NCAA Tournament for the third straight season.

Smits was in the middle of his second season with the Indiana Pacers and finished the ‘89-90 campaign averaging 15.5 points per game. When he walked onto campus in 1984 as a gangly 7-foot-4 freshman, no one could’ve predicted his incredible success in and after college. After hearing his name called second overall in the 1988 NBA Draft, Smits played 12 seasons with the Pacers before retiring in 2000.

Smits is the greatest men’s basketball player in Marist history by an incredibly wide margin. Without him, Marist could very well still be looking for its first NCAA Tournament appearance.

Smits wasn’t the only player to enjoy a professional career. Pecarski returned to Poughkeepsie in the fall of 1988 and averaged nearly 20 points per game in his final season at Marist. He also lasted until 2000 in the pros, bouncing around in Greece, France, and Spain.

Players like Pecarski, Krasovec, and Rudy Bourgarel all retreated back to Europe, where they fell out of touch with their old teammates. The rest of the team and some of the coaching staff has stayed in sporadic contact with one another over the years.

Jovicic, the assistant coach involved in many of the violations, stayed on the coaching staff until 1989, serving five seasons under Magarity and Matt Furjanic. The news of the penalties for the violations was crushing to him. He spent a brief stint in a psychiatric institution and was bitter about the NCAA’s ruling for years.

He worked for the athletic department until his death in 2004 at age 52.

Magarity continued to coach at Marist until 2004, stepping down to take an administrative job with the MAAC. After Smits and the NCAA penalties, Magarity couldn’t find the same success as he did in the first few years of his tenure.

Though few people would probably admit it, the NCAA’s sanctions impacted Marist far beyond the two-year enforcement period.

After the ‘87-88 season, Magarity’s teams tended to hover around the .500 mark. He only registered one more postseason appearance, a trip to the NIT in 1996. He went 253-259 in 17 seasons at Marist.

He returned to coach women’s basketball down the road at West Point, assuming the head role at Army from 2006 until his retirement last year.

The longest holdover from the Marist teams of the mid-80s has been Tim Murray, who left Magarity’s staff after the ‘88-89 season but became his boss after being named Marist’s athletic director in 1995.

Under Murray, Marist has become a more well-rounded athletic institution, but the men’s basketball program has crumbled in the last decade-plus of his tenure.

After a brief resurgence under Matt Brady in the mid-2000s, which included another NIT trip, the Red Foxes fell into a funk from which they have still yet to fully emerge.

Since the 2008-09 season, Marist’s record is 126-301. The Red Foxes haven’t even won 30 percent of their games in the last 13 years.

Marist hasn’t made the NCAA Tournament since 1987, 35 years this March.